Features

Americans Parade featured in American issue of Whalebone magazine

A photographer visiting from England finds us both divided and united at the same time along parade routes.

Americans Parade in China Newsweek

The feature is interesting as it focuses a lot on the historical culture of different parades as well as America today.

An image from Americans Parade published in Philosophie Magazine, France.

Interview in El Pais

British photographer George Georgiou toured the United States in search of parades, composing a portrait of the different communities that make up the nation, which in turn delves into the loneliness of the individual by GLORIA CRESPO MACLENNAN

Interview and review in ASX by Eugenie Shinkle

The resulting images are immensely detailed. You need a long, slow look to get the measure of them: the landscapes, the pictures-within-pictures, the glances exchanged between spectators, their clothes, their gestures, their expressions. It also takes time to fully appreciate the range and depth of photographic tradition packed into each one. Every image poses the question of American identity not just from the standpoint of our present reality, but from the playbook of iconic images – most of them from the twentieth century – that make up the history of American photography.

Americans Parade: The Faces of the 21st Century by Colin Pantell in PH Museum

We don’t get just one beaded Mardi Gras parade, we get several; there are the beaded celebrants packing the sidewalks in downtown New Orleans, set off against the parade watchers gathering beneath an overpass in a suburb of the same city. The day might be the same but there are also environments, life stories, and urban histories contained within these images that point to a very different experience. In the book, the images are two dimensional, but the faces, surfaces and textures that you see are like little beads of sweat on the page, hinting at the organic depths that lie deep beneath the paper. The manner in which we see, read, and understand images cuts through history and time.

Feature in Photonews, Germany

Americans Parade in Fisheye

Meetings in a divided America. With this parade of Americans, the artist composes a photographic fresco detailing the nuances of these ephemeral communities.

Townsfolk on Parade by Sean O’ Hagan: Observer New review

The British photographer’s new book picturing onlookers at events across the US in 2016 sheds an unexpected light on the fractured nature of contemporary American life

“Americans Parade, from it’s deftly chosen title to its formally democratic approach, is a book that repays close scrutiny. It is a portrait of not one America, but myriad often contradictory Americas. Perhaps, it was ever thus, but those contradictions - of class, race, economics and ideologies - seem starker than ever.

Americans Parade featured in The Atlantic

In Georgiou’s photographs, these celebrations remain outside the frame; his lens stays trained, instead, on the sidelines, and on the spontaneous tableaux assembled there. Some of the watchers captured in his images are clearly driven by passion or commitment. Some appear just curious; others seem deeply bored. Some look like they might disagree with one another. And yet the very existence of each group portrait produces an illusion of unity, as if the people in each frame, at least for that instant, cohere. Maybe an act as basic as standing alongside other people still counts for something. Maybe photographs of us doing this, however fleetingly, count for something too. — David Campany

Book review of Americans Parade by Loring Knoblauch in Collector Daily

“Americans Parade is an inspired example of the power of seeing something obvious from an alternate perspective. Watching the watchers turns out to be surprisingly compelling, and Georgiou’s compilation of disparate parade crowds offers an unexpectedly insightful composite portrait of 21st century America. This single subject photobook essentially catches us off guard, thereby documenting truths about who we are and how we behave that we might not have noticed ourselves.”

PORTRAIT OF A NATION by Max Houghton in B&W Magazine

In this body of work Georgiou employs photography to its best ends: he captures something important, but fleeting, and makes it endure. Through this series of portraits of many varied communities, the achievement of the work at this significant moment in history is no less than the portrait of a nation.

In the company of strangers: A portrait of Americans as they come together on U.S. streets by Olivier Laurent in the Washington Post

An Assignment for the NYT’s Magazine on Basketball in India

Scenes from a crowd by Alice Zoo in the BJP

In his latest project and soon-to-be book, George Georgiou finds anonymity and intimacy along the roadside of American parades

“Georgiou was able to access a surprising kind of intimacy with his multiple subjects: the intimacy of unguarded self-presentation, the purity of revelation that emanates from a person who is unaware of being looked at.”

Where America’s ended up: Corriere della Sera Sette

FaultLines/Turkey/East/West published alongside 8 Turkish writers in Respect magazine, Czech Republic.

StreetView: New York Times Magazine

When I first started working on Americans Parade I showed The NYT’s magazine some of the early parades. They believed in the project and commissioned me to continue working, generously supporting the project until the end. The feature was published on the weekend of Trumps inauguration.

Commission for the NYT’s Magazine on the Chinese economic expansion in Namibia

Assignment for Bloomberg Business Weekly magazine

Give Us Your Tired, Your Poor, Your Huddled Masses Yearning to Send Cash.

Western Union built its business on refugees and immigrants. Can it survive the political backlash against them? By Drake Bennet and Lauren Etter

How to steal a River, commission for the NYT’s magazine on illegal sand mining in India.

Black Sea, a commission from the NYT’s magazine for their Voyages issue

‘‘A few years ago, a friend of mine bought a couple of buildings in a little Bulgarian village called Mandritsa. The village is beautiful, and it has incredible fruits and vegetables. I’ve got my own place there now, and that was my destination this summer. I started in Ukraine, where I’ve been working on another project. Along the way, I wanted to revisit some cities by the Black Sea that I hadn’t seen in years. This is one of the poorest regions in Europe, but there is an emerging middle class, and in summer you get people from all over Eastern Europe and Russia coming in for a budget holiday. I’ve mostly seen the Black Sea out of season, when the feeling is more melancholic, but summer changes everything.’’

Interview with Fotoroom

Last Stop — George Georgiou Photographs the Streets of London from aboard Its Buses

54 year-old British photographer George Georgiu introduces us to Last Stop, a body of work he made shooting from London’s world-known buses that is also available as a self-published photobook selected by Martin Amis as one of ten best photobooks of 2015 –

Hello George, thank you for this interview. What are your main interests as a photographer?

I’m generally a fan of a lot of different genres of photography but If I start to look over my work, there are without doubt recurring themes and subjects I keep coming back to. I would say that I am fascinated by public space, particularly urban space and our interaction within that space. The interaction is crucial to me, from a political and social viewpoint but also from the personal and emotional, and how it shapes perception.

How did you get the idea to photograph London from inside its renowned buses?

The work evolved from an earlier project. In 2005 I went to Ukraine to look at life after the Orange Revolution. As the country is going through a transition or a method of transit from one system to another, I thought it would be appropriate to play on this notion of transit by moving through the country on public transport, photographing as people move from home to work, shopping, going out and selling goods around the transport hubs. This allowed me to move through the towns and cities in a random manner, photographing from buses, trolleybuses, trams and trains the daily lives of Ukrainians, moving from the centre to the residential areas and city outskirts and back.

I was curious to see if the images would take on a similar feel if I replicated the approach in another country, so I photographed from buses in Istanbul. Instantly, I noticed that the way people use the public space in Turkey – the way they interact with each other and the environment – was very different. When I moved back to London, my home city, after being a few years away, I was fascinated by how much it had changed. The bus seemed like the perfect way to frame a city, to make something coherent and to encapsulate my ideas.

What was your main intent in taking the Last Stop pictures? What are you trying to communicate with these images?

There were so many ideas floating around in my head. Originally I was thinking about London as a city of migration, the last stop not only for immigrants but also for people from across the UK. A city of dreams and possibilities; but as we all know, these dreams are not so easily realised. As the project evolved, I became more interested in trying to express the experience of the city, how we move through it, share it, coexist as a diverse group of peoples and cultures. The hardest part was what I consider the little soap operas we see everyday in public space, those encounters we witness and perceive as fictions – are they secret lovers or a married couple? etc. It’s a little like when we drive pass an accident on the highway: we glimpse the crashed car and imagine the rest. How we perceive became an important element in the work.

The images of Last Stop seem to straddle street and surveillance photography. How would you describe them?

Surveillance was on my mind when I was making the work and the aesthetic plays with the look of Google Street View. Surveillance in the city is all around us but on the flip side of this is also our sense of invisibility, how we allow ourself to express very private behaviour in public space, like a family argument. I am always amazed how people talk so loudly on their mobile phones in confined spaces, or how in a popular restaurant chain in the USA, I feel like I am sitting in the lounges of 20 different families during meal time. So me sitting and photographing behind the window of the bus is an act of surveillance, invisibility and voyeurism, all inter-related acts of seeing in the city and in photography.

I see Last Stop as straddling street photography, surveillance, landscape and documentary fiction.

Is there anything you realised about London or even humanity while working on Last Stop?

Yes, our ability to share space and coexist.

Did you have any specific references or sources of inspiration in mind for Last Stop?

My main reference and inspiration is my own knowledge and fascination for London over the years. I used to travel around London on buses as a teenager with friends during the school holidays, sometimes with an aim but often just for fun. And over the years I have lived and visited a lot of different neighbourhoods, witnessing the changes that have taken place over the last 40 years.

Other references are more from the narrative construction of movies. I love the opening sequence of Down by Law by Jim Jarmusch and intertwining films like Crash, Magnolia, Traffic and Amores Perros. And finally the 1976 John Smith video, The Girl Chewing Gum shot in Dalston.

Please talk a bit about the Last Stop book.

The design of the book was by far the hardest part of the whole project as it holds together the whole concept of the work and relates to the actual experience of moving through a city.

The essence of the project is that you might take the same route everyday but what you see, the ebb and flow on the street takes on a random nature. To capture this flow, the concertina allows the feel of a bus trip, but more importantly it gives the viewer the opportunity to create their own journeys by spreading the book out and combining different images together. This moves the book away from an author-led linear narrative to one of multiple possibilities.

I struggled with the design and selection for a long time but I felt that I had to take responsibility for the whole project. It was the same with self-publishing and doing a crowd-funding campaign. Because of the expenses of making a concertina book and with all the hand work that it involves, I didn’t want a third party cutting on the production values because of costs. I was lucky that I found a great printing house in Istanbul, MAS matbaa, that worked very closely with me on the technical aspects and helped make the book financially viable.

What have been the main influences on your photography?

Too many to mention. I have been a big fan of photography for well over 30 years and my influences have constantly changed over that time. Outside of photographers, I think my politics, film and my wife, Vanessa Winship.

Who are some of your favourite contemporary photographers?

In the last 4 or 5 years I haven’t engaged in looking at photography so intensely and there are too many photographers to name. Generally, I am a big fan of American photography – artists like Philip Lorca di Corcia, Larry Sultan and all the others from that generation. I like the engagement of South African photographers Guy Tillim and Mikhael Subotzky. In Britain, Paul Graham and Stephen Gill. Of the new generation I am very impressed by the work of Max Pinckers. And finally Vanessa Winship. I have sat and looked at her work for years and I never tire of looking at its keen poetic quality.

Article here

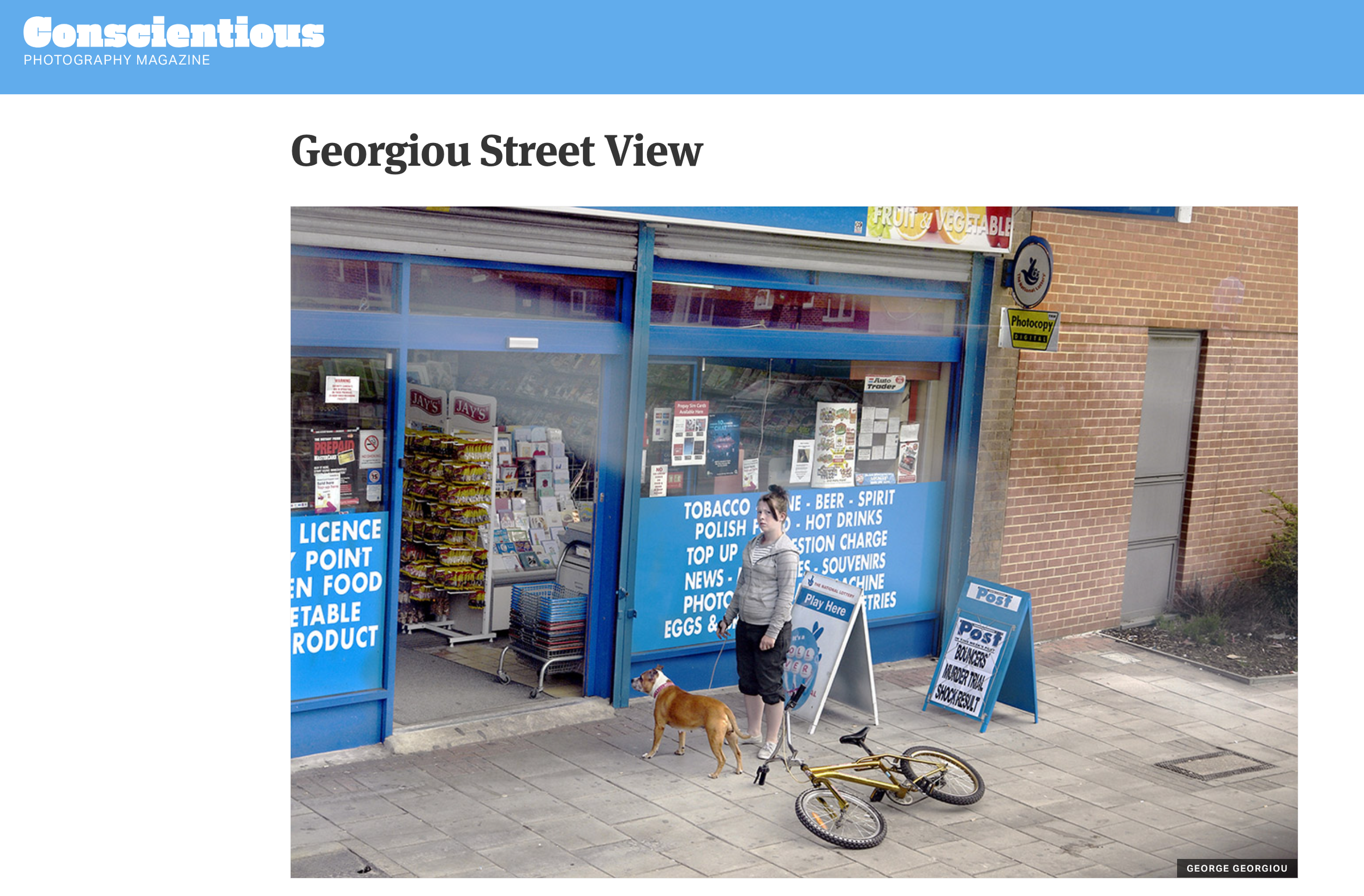

Review of Last Stop in Conscientious Photography Magazine

A few years after photographers started working with Google Street View (GSV), we are now at the stage where things have started to get interesting. As with every new digital photographic tool, the real question always was whether there would be more serious work after the initial wave, which was simple, one-dimensional, and thus fairly superficial (the hype being produced around it notwithstanding). Unlike in the case of “Second Life” photography (anyone remember that?), there was. Artists like, for example, Viktoria Binschtok started to engage with GSV in ways that pushed the boundaries considerably.

But much like the move towards digital photography has resulted in a strong counter-movement towards physical objects (say, in the form of photobooks), we are now also seeing examples that explicitly or implicitly push against the idea of being relatively passive consumers of robotic photography. Jim Goldberg was spotted sitting on top of an RV in New Haven, photographing people and locations. And there is George Georgiou taking the bus in London, surveying the city along its routes, and taking pictures for what has become Last Stop.

Now, whether or not GSV and Last Stop are directly connected doesn’t really matter. Given Last Stop visually operates along the lines of GSV, a connection can – and possibly should – be made. What ultimately matters the most, though, is what Last Stop tells us, and what the repercussions are for bodies of work based on GSV.

Just to be clear about this, I don’t belong to the camp that thinks photographers have to go out into the world to take pictures. It’s perfectly acceptable to gather them on your computer. But, and this is a big but, first the work has to amount to something, regardless of how you assemble it. And this is where a lot of the GSV work, especially of the earliest wave, has remarkable problems. Second, the fact that the photographer is physically absent from the scene also plays out differently for different types of work, in particular if there is overlap with documentary photography, say, whose traditions and ethics cannot simply be ignored or even thrown out (just as an aside, I often feel that artists in thrall of some new technology are too eager to have that simple fact top all concerns of their medium’s history – I find this extremely problematic).

The following always is the ultimate test for any photographic body of work: does it amount to something, to anything? It’s hard, if not impossible, to predict whether it will have lasting power. But to ponder what it amounts to helps at least understanding whether it might have lasting power, whether, in other words, it’s something worthwhile getting back to again and again.

In terms of how it was made, Last Stop – which is available in self-published book form – is simple: using London’s double-decker buses, the photographer traveled across the city, taking pictures of what presented itself to him. There are photographs of people, quite a few of them, going about their business, whatever it might have been at the moment the bus passed by. And there are a few cityscapes or fragments thereof, providing context or speaking of what people who are now absent might have done before.

The book presents the work in what might be the most obvious and certainly the most appropriate form, an accordion. This folded, long strip of paper takes the viewer along on the ride, moving her or him from London’s center to what appear to be its outskirts or at least its less crowded forms. On each side, the flow of the images is changed up twice (remember, an accordion book has two sides), with images being on the “spreads” shifted. Consequently, there are short sections that flow slightly differently, that, in fact, present small vignettes of pictures playing off one another. Producing these sections was an incredibly smart decision, given it breaks the flow a little, and it drives home the point that an accordion has its own logic (my apologies for the “driving home” picture in an article on photographs made while riding a bus).

Given one can unfold parts of the accordion at any time, the sequence is possibly even more crucial than in any regular book. The viewer can decide to see two, three, four photographs at any given time (unfolding the whole beast would require a fairly large space, though). So the sequence has to work well, but it also cannot be too simple. The sequence in Last Stop achieves this goal beautifully.

Looking through the book clearly presents a narrative of life in the city and of people interacting with other people, under a large variety of circumstances. There are sub-narratives in the work that weave in and out of each other. For example, there is a section on looking – photography effectively is a way of looking, and the section openly acknowledges this by making it a subject of the photographs.

Last Stop is a smart book, but it is more than that, given it does not aim at making its maker’s smartness one of the main aspects. The book also is very engaging, without trying to be entertaining. Not that being entertaining necessarily is wrong, but the problem with all the entertainment photography that has started to fill larger and larger segments of contemporary photography is that it’s shallow (and there’s something very wrong with being shallow). There also is no pandering to expectations (at least as far as I can see – maybe Londoners will disagree).

Instead, much like I imagine a bus trip through a city might be, the photographs reveal themselves as discoveries that, however, aren’t completely random. Now that’s a high bar to cross, and Georgiou has done it extremely well. And this then tells us something about how we can (maybe should) approach Google Street View photography.

Striking photographs from a London bus, BBC Culture by Tom Seymour

In his series Last Stop, George Georgiou photographs striking ‘micro-dramas’ around London – all from one of the city’s iconic red buses.

For more than 10 years, George Georgiou lived largely in his car. From a five-door hatchback, the native Londoner of Greek Cypriot descent and his wife, fellow photographer Vanessa Winship, travelled across Ukraine, Georgia, Turkey and the US – and shot pictures everywhere they went.

Three years ago, Georgiou decided to return home. He settled in Folkestone, close to the Channel Tunnel. On a homecoming to his native London, Georgiou caught one of the city’s red buses.

Observing from the window, he says, he was struck by the “profound state of flux” of the city of his birth. He had always called London his home – but now he hardly recognised the many new veins of the city, the ceaseless crowds, the rising new homes, the churning humanity.

George Georgiou’s photographs were inspired by “seeing so many people living together, and, mostly, making it work”, he says (Credit: George Georgiou)

“London had quite suddenly become the most international place on earth,” Georgiou says. “It had opened up to people who have no heritage or connection in London, apart from their wanting to make this their home. Seeing so many people living together, and, mostly, making it work – I found it very powerful.

For many, many people, London had become the last stop, the final destination on a long journey – George Georgiou

“I realised that, for many, many people, London had become the last stop, the final destination on a long journey, the Holy Grail of the Western dream,” he says. “I wanted to try and understand this: the way people share the city, the everyday movements, the rhythms and rituals of the city.”

From a bus, Georgiou was able to capture the rhythms of daily life in London (Credit: George Georgiou)

And so Last Stop was born. Entirely crowd-funded, it is a remarkable photographic assessment of London, taken from the perspective of the city’s iconic buses.

Fleeting moments

Arriving in London from the south coast, Georgiou would board the first bus that sparked his curiosity. “I wanted to explore the whole city,” he says, “from the centre to the suburbs. East, west, north and south.”

He would spend up to 12 hours a day riding bus routes’ entire length. “Sometimes, I would see a destination on a bus I hadn’t heard of before, or my familiarity was the name of the place on a map,” he says. “My curiosity would always make me pick that bus and follow it to the end of the line.”

Georgiou’s subjects, involved in what he calls “micro-dramas”, rarely even knew he was photographing them (Credit: George Georgiou)

Taking whichever seat was free, he would stare into the right-angle viewfinder of his camera resting on his lap, so that his subjects were oblivious to the lens trained on them.

Georgiou began to view his photographs as "micro-dramas”. Each one froze a pregnant moment in strangers’ lives – caught fleetingly and randomly by the movement of the bus.

I would see tiny scenes that could have been taken from a soap opera – Georgiou

“I would see tiny scenes that could have been taken from a soap opera,” he says. “A small interaction or dynamic, an embrace, or an argument, a glance at another, or a moment of total solitude. I would find myself inventing narratives for the people I photographed,” he says.

Georgiou would take a bus from one end of the line to the other, passing apartments, council estates and suburban homes (Credit: George Georgiou)

In one image, a couple stand stiffly opposite each other, holding hands yet keeping their distance. In another, an old woman seems to exchange a cigarette for something with two young men. An argument breaks out in an upmarket restaurant. A homeless man awakes, confused from a dream, on the edges of the wet streets. Children chase a huge balloon in the grounds of a council estate. An elderly gentleman stumbles along a busy road.

Sometimes Georgiou was close enough to touch his subjects (Credit: George Georgiou)

The photographs of Last Stop are searing in their intimacy. Georgiou, sat by the window, was often “close enough to touch” the people he photographed, he says. Only the window pane and his camera lens separated him from his accidental subjects.

Dramas from a distance

There’s an element of voyeurism here, a certain exploitation of private moments in public places.

In a city, we’re always looking into other people’s lives – Georgiou

“But this voyeuristic aspect is crucial to the experience of the city,” he says. “In a city, we’re always looking into other people’s lives. We all do it, but this voyeurism is what makes living in the city so beautiful; all this humanity and never-ending narratives and dramas. That’s why I love the experience of London, these small, random encounters, micro-dramas caught from a distance, allowing us fill the gaps.”

Voyeurism is an aspect of Georgiou’s photographs, but also of living in a city, he says (Credit: George Georgiou)

What’s striking, Georgiou says, is how intuitively we understand many of these moments. “With my camera, I can freeze these dramas,” he says. “But, looking back, we all know what’s happening. We can instantly recognise the emotion in the images.”

Last Stop is not purely about people. When Georgiou settled on the upper level of a bus, he allowed himself a broader view, situating the micro-dramas in their architectural context.

Georgiou’s photography explores how public spaces allow people to be solitary, but not in isolation (Credit: George Georgiou)

This triangulation between street portraiture, architectural studies and the landscape is a key aspect of Last Stop.

“Rules of interaction and proximity are changing, between what the French anthropologist Marc Augè calls non-places,” he writes in the introduction to Last Stop. “These public spaces are designed for people to move through in solitude but without isolation, layered against an organic historical city with deep traditions, where old and new are interwoven.”

“Rules of interaction are changing”, Georgiou says (Credit: George Georgiou)

After a successful Kickstarter campaign, Georgiou published Last Stop independently, selling copies through his website from his home in Folkestone. The photographs were published using an innovative “double-sided concertina” that allows us to view the images in any order we choose. Every time we leaf through the pages of Last Stop, a new sequence of images unfurl.

“I wanted to find a way of staying true to the experience of staring out of a bus window – the serendipity that lies behind such micro-dramas, of how we grow accustomed of sharing space with so many others, so many separate, complex lives,” Georgiou says.

“For I am part of this rhythm and community,” he adds. “It is my community, my security, my home.”

Last Stop feature in D2

British photographer George Georgiou’s haunting images of modern Turkey show a country of marked contrasts.

Review of Fault Lines in Atlanta Journal-Constitution by Felicia Feaster

Whether in his landscapes or portraits, Georgiou has a way of wrapping his subjects with devouring expanses of space — lots of sky, mountain ranges and long dusty roads that emphasize a feeling of loneliness that weighs heavily in his photographs.

Last Stop featured in M Le Monde magazine

Last Stop featured in Time Lightbox by Sonia van Gilder Cooke

“To be sure, London's council estates and suburbs lack the obvious appeal of its famous monuments. But Georgiou says the city is defined as much by transition as tradition.”

Last Stop in Professional Photographer

“Once you focus, you know what you’re looking for,” he begins. “I started to look for different images, and that was what pushed me to carry on looking for the scenes that I call micro dramas, little soap operas where there’s a communication between people and you’re not quite sure what’s going on in those pictures. They have narratives but the narratives are open to interpretation.”

My work from Leicester featured in Caravan.

Leicester feature for Russian Reporter

A few weeks ago I shot a feature for Russian Reporter on Leicester, the 10th largest city in the UK.

The story was based on the prediction that Leicester will become the first city in the UK with a non-white majority. I was free to explore and interpret this story as I saw it.

Turkey in Epsilon Magazine, Greece

Newsweek

Newsweek used my triptychs from Istanbul in the way they are intended to be seen, good to see a magazine respected the photographers vision.

‘Fault Lines: Turkey/East/West’ showing at QUAD during FORMAT 11

George Georgiou is a prominent photographer, who was featured in the main gallery at QUAD during FORMAT11 with ‘Fault Lines: Turkey/East/West’ - a series that examined a country which was rapidly modernizing and changing, taking influence from western civilization whilst retaining its strong eastern culture. The book is still available in Quad book store, and is a fascinating project. George took some time to talk to us about the work and his practice.

Hi George, could you tell us a little bit about how the concept for ‘Fault Lines: Turkey/East/West’ arose?

I was living there 4 ½ years, and when I moved there I already wanted to do something about contemporary Turkey. I didn’t want to sort of romanticise Turkey in the way that it often is. I had my eyes on what was happening whilst I was there. The project was shot in the last 2 years I was there. The first 2 and a half years was when I was starting to understand what was happening in Turkey and starting to see the issues involved in politics and peoples concerns. And that tied in with the new government, which is still the present government.

I was sort of working in a diagonal across the country. I started a project in the East, and each time I went backwards and forwards to the West, I started to see new towns appearing out of nowhere. There had been 1000 housing units built in the past 20 years and suddenly, it was happening in mere weeks. That aspect of modernization was a part of the concept and fed in to my interest in to what East/West meant. We use these words all the time, but they depend on where you come from. I was thinking about whether we apply ‘West’ when we actually mean ‘modern’ and then on top of that, there were fault-lines in Turkish society that underlined the work. They’re a little bit harder for people to read if they’re not familiar with Turkey. But the project works on a global level, looking at this modernization, architecture, and the developing spaces which we’ve seen occur all over the world.

In terms of what you photographed, was it relatively straight forwards in terms of researching and photographing particular locations, or did you almost come across these scenes by chance? A lot of the images resemble that street photography style that FORMAT11 showcased.

I stumbled across a lot places, but because I did it over this two year period, I returned to a lot of places too. There were particular places and cities that I would go back to again. But in terms of individual pictures, I did want to stumble across these scenes. So I think that if you do enough hours of travelling then something will appear. Such as the photograph of the man on a roof top, hosing, which may appear to be posed or staged initially.

How does the work fit in with your other projects, which have seen you photograph amongst more dramatic and risky situations, such as scenes of conflict and war. How does this body of work fit in with that other style?

My work consistently looks at these urban and public spaces, throughout projects.I think that in a sense, I made quite a drastic change by moving to Turkey. Before that, I was a black and white photographer. I also did a lot of work in Kosovo and Serbia, and that was very tense and emotional, both during the conflict and after the conflict. But that was all emotionally charged, so at the time, I felt that it was the right language to use. When I moved to Turkey, I felt that I couldn’t use that same language. It wasn’t dramatic or the same emotionally charged scenes. I had to find a language, and I moved to colour photography.

Would you say that there’s still some tensity to the ‘Fault lines’ though, as you capture this politically tense time, and time of great change, so you still carry through that language?

There are overriding themes with my work, which we can see when we go back to the black and white. I have a strong interest in how people interact outside and keep in their own headspace, and so I can select work from throughout my career and make a coherent edit of images that would go together have a consistent theme throughout.

With the Turkey work, yes there is a political charge to it, because politics are always of personal interest to me. When I finished the work, the sequencing of the work and the book is important to the reading, so as to ensure that this theme doesn’t always take the forefront.

Tell us about your journey with photography. When did you first pick up a camera, and how did it become a profession?

It was very slow! I did an O-level at school, I don’t know what that is now.

GCSE maybe?

Something like that. I had to do an extra subject, so I did it thinking it’d be some cushy, non-academic class. And I got an ungraded level for it. Which is worse that a fail! But I became interested and called myself a photographer, even though I probably wasn’t, but I was going around making pictures. And so I started to study photography in few different places.

I went to Bournemouth, which was an amazing place with a lot of fashion and portraiture happening. Then I went to Sir John Cass Arts Centre in Whitechapel, which at the time ran a part time course where you could just pay £1 if you were unemployed for the year, which was an amazing course. A lot of London photographers would come in and spend the day with you, and everyone was encouraged to be doing their own thing and work in their own way. It was around that time that I made my first serious photographs. Then I went to what is now Westminster. A majority of the course there was theory. When I left that, it took me about 5 years to recover, and since then it has been something of a slow journey.

I do find it interesting to speak to photographers who come to photography late, or weren’t initially interested by the camera but have come to discover it through a change in environment or such. As a photographer in the world of documentary and photojournalism, what role do exhibitions and festivals play in your career?

Now, quite a lot. I don’t do so much photojournalism. I do the occasional magazine assignment. A lot of the work I was doing in Turkey, I would tell the magazines up there about what I was doing and then maybe they’d buy into it. I don’t like very much working to other people’s ideas, especially if it’s a place that I know well. I don’t want some other story to go over it. So maybe 2 or 3 times a year I’ll work commissions.

Exhibitions, festivals, selling prints, workshops is much more my practice. And if I have a finished work, I can sell that to magazines and publications.

It’s always interesting to hear about that balance between personal work and getting commissioned for it, and doing commissions which you might not feel has much strength. I sometimes think it might be a case of beggars can’t be choosers, but then find it really fascinating when people can get commissions for their personal work. And like you said, you make the work and tell people about it, who get interested in it, do they give you assignments towards that work too?

They mostly buy in to it. When I was doing the Turkey work, I had a couple of people report in, and I sold a lot of it as features to magazines in different countries. And it has different sides. There’s a side of very urban imagery and also work which is very intimate… there’re also these grids of portraits against blue skies, so it gives the designers plenty to play with.

I was looking at Turkey in a contemporary way, and so I knew that the work would always be relevant today. I finished 6/7 years ago but I’m still exhibiting that work. I think because I started to work on very global issues and questions, it has a different lifespan. Often reportage has a focus on one event, and the work lives for as long as the event does. So I have found myself avoiding that.

What photographers inspire you? Not necessarily in their photographers, but perhaps in their approach and style.

My wife! We’re constantly bouncing ideas off of one another. We went to college together. We’ve assisting each other on projects, we travel together, etc. When most people are working in photography and it’s taking a long time for them to get to where they want to be, they give up. But when there’s the two of us and we’re in the same boat, we keep each other going.

In terms of other photographers, there’s too many to mention. They change all the time. Starting out at 21, I was looking at Diane Arbus and Robert Maplethorpe, who were very important at that time. And Cindy Sherman. When I was more in to reportage, it was Eugene Richards and a whole array of similar photographers.

How did you initially discover FORMAT festival?

I think they contacted me actually, I was part of the group show. I’m not so involved in British photography, so I tend to work more outside of Britain. Maybe its because I’ve spent so much time outside of it.

Did you visit the festival, and what were your thoughts on the festival and the city?

I really enjoyed the festival, I hadn’t been to it before but I had been working near by in Leicester on a commission. I like the fact that it’s quite compact. There are the portfolio reviews, which draw a lot of people in, and the whole festival is very intimate. I think I prefer festivals of that size rather than the big ones as you get to see everything and meet people properly, as opposed to maybe Paris photo.

Where the amount of work can be quite overwhelming.

Yeah and you’re constantly seeing people and going to things, but you don’t actually get to see anything. In Derby you actually get a chance to sit down with people. The city is quite interesting, I like the way some of the venues are close together in the centre of the city, and on the opening nights you have the photography people immersed in with the very British nightlife. So the whole thing is very interesting and cultured.

I do like to hear from what people think about a major international festival of photography which isn’t in London.

Well in London there’s not actually that much in terms of festivals. If you look at most countries, the major festivals aren’t in the capital cities. But in Britain there is some reluctance for people to travel outside of London, even to Derby, which isn’t that far. But maybe that’s also to do with the economics to how festivals work. In France there’s often a budget to ship in people to the event. But then that would be down to the culture in France to give funding to these artistic events.

You kind of touched on it already, but what is your opinion on the role of photo festivals in contemporary photography?

For me, festivals are awesome. There are a lot of them but there’re a good opportunity to be introduced to work and see things - especially the festivals which reach out worldwide to source photography. You can have very interesting debates, so to me they’re very important. And also they’re an opportunity to meet the practitioners which you don’t really get at an exhibition. Usually people go up for a few days and spend a lot of time there.

Anything lined up for the future you’d like to mention to readers?

At the moment I’ve been preoccupied with a book that I’m working on, which is finished, but self published. When you self publish, you also have to deal with things such as shipping, which is also what’s great about it. I’ve had a lot of communication with the people who are buying the books, which you don’t usually have if you are published with someone else. It’s a direct communication with the audience, which I’ve only ever had with an exhibition, but not in the same way. I’m also currently working on some stuff in the United States, so look out for that.

NYT’s LENS

“Through a series of haunting architectural and landscape scenes of Turkey’s rush toward modern-isation — and the resulting tension between the secular and the modern — George Georgiou has visually put his finger on a kind of listless alienation which at times can seem to pervade globalised society. Turkey, traditionally a bridge between East and West, seemed a logical choice for such a cautionary vision.

His latest book, “Fault Lines: Turkey From East to West” (Schilt Publishing), forces us to consider not so much the emotions that connect us, but rather the spaces that separate us.” By Adam Stoltman

Fault Lines in 24 magazine, Italy

Fault Lines featured in the New Yorker

Fault Lines in the Sunday Times, UK

The Contact Sheet by Steve Crist

I have a contact sheet and the selected image in a new book on the contact sheet.

Featuring a diverse collection of original contact sheets from over forty international photographers, The Contact Sheet allows in-depth insight into the subject matter and the photographic process -- often revealing a deeper story that has not been told.

Featuring over forty international photographers, including: William Claxton, Chuck Close, Michel Comte, Anton Corbijn, Imogen Cunningham, David Doubilet, Elliot Erwitt, Nan Goldin, George Georgiou, Nadav Kander, Art Kane, David Hume Kennerly, Dorothea Lange, Saul Leiter, Peter Lindbergh, Jerry McMillan, Joel Meyerowitz, Richard Misrach, Arnold Newman, Paul Outerbridge, Martin Parr, Ed Ruscha, Julius Shulman, Jeanloup Sieff, Jerry Uelsmann and William Wegman

Fault Lines in BJP Parallel Lines by Colin Pantall

“ ‘Happy is he who calls himself a Turk’, goes the saying. George Georgiou’s work, however, reveals a more complex sense of national identity, struggling to reconcile it’s multiple personalities”

In the shadow of the bear featured in FT magazine

Interview in Hot shoe magazine

20 page feature of Fault lines/Turkey/East/West in Geo magazine, Germany

Fault Lines in Rear View Mirror

Last Friday in Milan a beautiful new Italian photography magazine was launched called Rear View Mirror, published by Postcart.

It features Pieter Ten Hoopen, George Georgiou, Marta Sarlo, Agnes Dherbeys, Alisa Resnik and Massimo Sciacca plu a couple of interviews including Guy Tillim

Turkey in Kapa Magazine, Greece

Transit Ukraine in La Vie

Transit ukraine Featured in Foto 8 magazine